Bioplastics are plastics made at least partly from renewable materials. They’re often suggested as an eco-friendly alternative to petroleum-based plastics – but the reality is complicated.

Why is it complicated?

The term ‘bioplastic’ is very loose. There isn’t much regulation around what can be called a bioplastic.

Ok, so what’s the definition?

A bioplastic is a bio-based plastic, which means it’s made at least in part from renewable components, such as corn starch, sugarcane or cassava sugars, or by microorganisms that use organic matter to produce plastic. Traditional plastic is made using fossil fuels.

But bioplastic is also sometimes used as a term for plastics that biodegrade – but these aren’t necessarily bio-based.

So not all bioplastics biodegrade?

Bio-based plastics may or may not be biodegradable or compostable.

Biodegradable plastics may or may not be bio-based.

(Don’t worry, it’s confusing for everyone.)

Some so-called bioplastics just degrade like petroleum-based plastics – that means breaking up into small pieces or microplastics, rather than breaking down completely without leaving any harmful residues.

Other types of plastic are marketed as compostable – but not always in your garden compost heap. Sometimes these materials are only compostable in an industrial facility using very high temperatures.

But are bioplastics better than regular plastics?

This is tricky to answer.

There are some advantages. Typically, bioplastics reduce fossil fuel use and some are biodegradable.

However, conditions and facilities for plastics to biodegrade aren’t always widely available, so bioplastics often end up in landfill sites or the ocean where they can have a similar lifespan to other plastics, create microplastics or release methane, a greenhouse gas.

In addition, crops used for bio-based plastics use chemicals such as fertilisers and pesticides.

These crops also require extensive land use and there’s potential competition with food production (especially if bioplastics were to be used more widely in place of traditional plastic).

Recycling bioplastics is also complicated. Where recycling is possible, it may require consumers to separate their different types of plastic.

Some researchers say we should avoid bioplastics as much as regular plastic.

What’s the fix?

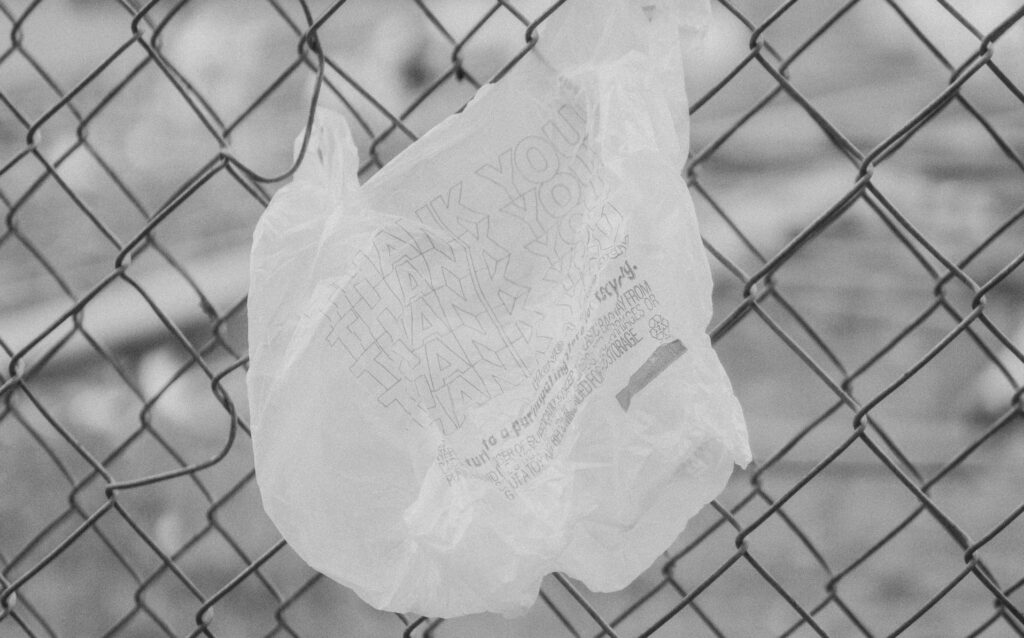

Not least due to the confusion around bioplastics, the best action is to continue avoiding single-use plastics – no matter how they’re made.

Maybe we’ll get to a point where bioplastics sit in less of grey area and are easier to identify – but unfortunately, we’re not quite there yet.

Globally, we need clear, accurate labelling and sustainability criteria for bioplastics. The EU has started work on a policy framework, which may serve as a model for others.

At home solutions

Replace single-use items with reusable alternatives wherever you can. Some easy things to switch out:

- Shopping bags.

- Water bottles.

- Coffee cups.

- Straws.

And for single-use items you need to use, look for other materials – for example, using paper cotton buds over plastic ones.

Sources

Columbia Climate School, The Truth About Bioplastics

Ensia, Are bioplastics better for the environment than conventional plastics?

European Bioplastics, What are bioplastics?

European Commission, Bio-based, biodegradable and compostable plastics

The Conversation, A type of ‘biodegradable’ plastic will soon be phased out in Australia. That’s a big win for the environment